Billy Hassell’s large-scale paintings depict perspectives and views of animals and nature we seldom or can no longer encounter. Deriving from images found in books and magazines, internet searches, and plein air sketches, Hassell composes engaging compositions that focus on Texas animal behaviors and habitats. Some of his subjects are now extinct or endangered—with titles using the descriptive “ghost” to indicate their current existence. Other animal subjects are ubiquitous and are vibrantly painted; yet the artist symbolically and subtly warns of the threats to their environments by painting their landscapes with a muted palette. The contradictions in depiction convey a sense of wonder and appreciation for the subject, all the while promoting dialogue related to the viewers’ important role in ensuring that all of Hassell’s future works don’t include the moniker “ghost of….”

Image: BILLY HASSELL, Ghost at the Window, Chisos Basin, Big Bend, 2021, oil on canvas. 60 x 72 in. Courtesy the artist and William Campbell Contemporary Art, Fort Worth.

Penumbra is generously supported by Carolyn & Karl Rathjen with additional funding from Pam & Bill Campbell, Scott Chase & Debra Witter, Susan & Jeff Jones, Matson-Chisolm Charitable Foundation, Pati & Bill Meadows/TLR Ranch, BB Moncrief, Sally & Robert Porter, and Barbara M. Williams.

Patrick Kelly, OJAC Executive Director and Curator, interview with Billy Hassell.

PK: Has your work always incorporated images derived from nature? Can you recall the first works that did?

BH: When I was about five years old my next-door neighbor, an elementary school teacher, gave me a big hardback children’s book, Birds and their Homes. I remember it had a 45rpm record in a sleeve inside the back cover with recordings of bird songs. As a child, I drew all the time. I drew pictures of pilgrims at Thanksgiving, cowboys and Indians “shooting it up,” Davy Crockett fighting at the Alamo—all the popular seasonal and historical heroes of my day. But I had an overarching curiosity and fascination with nature. The book of birds, which I actually kept until just a few years ago when I passed it on to one of my children, inspired a keen interest in birds. Before I ever set foot in a classroom, I was making drawings and cutouts of birds, nests on branches, and leaves on our kitchen table. One of the first drawings I did in grade school, after a field trip to Cleburne State Park, was of a deer which may have been my first sighting of a wild animal of that size. My first etching in college was of a fox; and soon after, a blue jay eating a monarch butterfly. I had no way of knowing then how threatened monarch butterflies would become. I had just discovered through an article in Scientific American that if a blue jay eats a monarch butterfly that has recently eaten milkweed then the blue jay will regurgitate the butterfly because the milkweed is poisonous. Thereafter the blue jay will avoid monarchs. This discovery, which inspired that etching, led to a new fascination related to food cycles in animals and the food chain as metaphor. Other works included coyotes (a spirit animal of mine), skunks, owls, snakes, fish, grasshoppers and birds—especially blue jays, crows, and ravens. Birds became a dominant recurring subject in my work for many years. They have come to represent all wildlife and nature. They are featured both literally and symbolically. I did not grow up with a lot of art around the house, but my family had a large collection of National Geographic magazines and a nice collection of Encyclopedia Britannica. There were frequent pre-school trips to the Dallas Zoo, Natural History Museum, and aquarium at Fair Park. I was disappointed with grade school because there weren’t enough classes focusing on nature.

PK: So why become an artist vs. a botanist, ecologist, or mammalogist?

BH: When I was still in grade school, I thought I might go into biology and become a herpetologist or zoologist. I didn’t really seriously consider being a full-time artist to be a real possibility, probably in part due to having been told that it’s virtually impossible to make a living as an artist. I was not encouraged in that regard by either my teachers or my parents. My interest in nature had always been driven largely by curiosity but with a strong visual component. I was attracted to the way things look. I was always drawing the things I brought home like turtles, lizards, snakes, fish, or other small animals. I had a biology teacher in the 5th and 6th grade that encouraged a more scientific method to my study of wildlife that included making detailed drawings. This nurtured my artistic growth. By the time I entered college and majored in art, I had come to the realization that the practice of art can be all encompassing. It allows the opportunity to integrate many areas of interest—biology, history, folklore, philosophy, ethnography, mythology, poetry and music—into my artistic projects.

PK: How do you approach creating a new work…finding image sources, making sketches, determining scale, etc.?

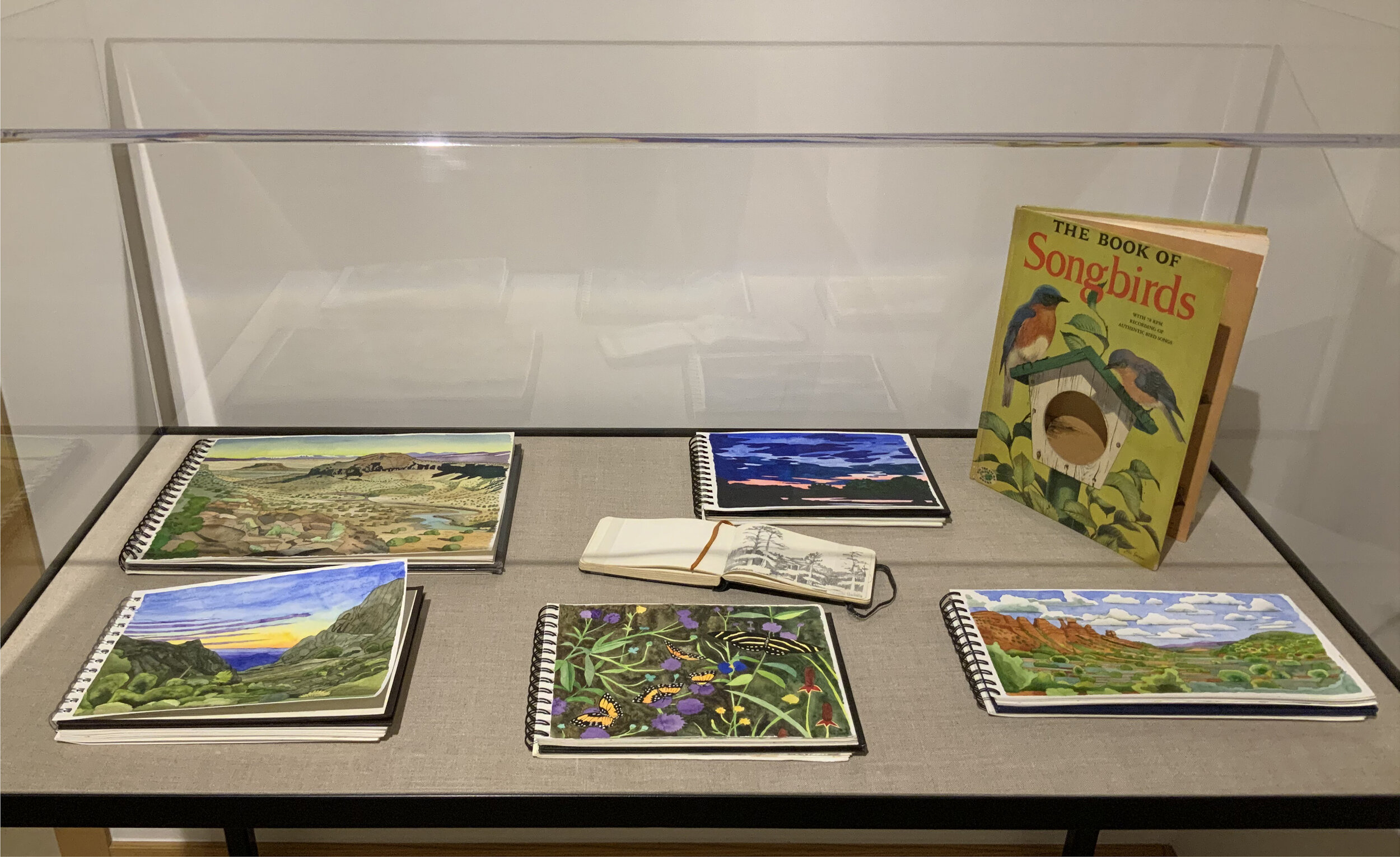

BH: Most of my paintings start with drawings or watercolors from my journals. When I travel, I keep sketchbooks and watercolor journals and I do a lot of plein air studies of landscapes, studies of birds and animals. I also create detailed drawings of birds and other wildlife in natural history museums—my two favorites being the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois. I’ve recently taken up digital sketching with an iPad since the pandemic, and I’ve added sketches of interiors to my repertoire.

The majority of the paintings selected for Penumbra feature birds that are either endangered or extinct and landscapes at risk. Caddo Lake and the Rio Grande, with their once pristine and fragile ecosystems, face all kinds of challenges from drilling, agricultural demands, and the “wall” along the Rio Grande. Rivers and lakes are common subjects that I return to again and again and the significance is the water. Rivers are natural corridors. Before railroads and the interstate system, they were the highways for commerce and travel. The landscape backgrounds in the paintings are all places that I have seen first-hand, drawn and watercolored on sight. The animals in my paintings have mostly been observed firsthand, except those that are extinct like the passenger pigeon in Ghosts of the Great Plains and the Carolina Parakeet in Ghosts of Caddo Lake.

I get ideas from things I read, and I do use some photographic sources—old field guides, books on natural history, National Geographic magazines from the 50s and 60s, and Scientific American. The larger paintings are based on small detailed drawings from my sketchbooks and watercolors. The compositions are figured out at that smaller scale and then are adapted to larger canvases. The scale of a painting is based on the subject matter, but often influenced by where it will be shown, or the impact, or presence I would like the painting to have in the context of my other paintings in a grouping. Though every painting has its own autonomy, there is an “installation aspect” to the grouping of several paintings as is the case in an exhibition. If the painting involves a panoramic view, I believe it should be at a scale to provide a corresponding impression of space to relate to the scale of the actual landscape. I’ve always tried, as often as possible, to paint birds and other wildlife at least life size (or larger). These ideas dictate the scale of a lot of my paintings.

PK: Recently your work has become less graphic and the color palette more subdued. Can you explain why?

BH: The main development in my recent work has been a more subdued color palette. The color reduction was intentional. The painting Canary (In the Coal Mine), 2018 was inspired by a quote from Kurt Vonnegut referring to artists and the role of art.

I sometimes wondered what the use of any of the arts was. The best thing I could come up with was what I call the canary in the coal mine theory of the arts. This theory says that artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They are super-sensitive. They keel over like canaries in poison coal mines long before more robust types realize that there is any danger whatsoever.

This “canary in the coal mine theory of the arts” got me thinking about making a painting to address that concept. I wanted to do a painting of a canary in a coal mine but didn’t want to treat the subject literally. I came up with the idea of placing a canary on a background of wildflowers, something traditionally associated with the concept of beauty except that the background would be painted in shades of gray and black to suggest coal or ash. That led to other paintings in shades of gray with minimal color that came to suggest a “world without color.” It came to represent what the world would be like without birds or other wildlife; what the effects of the extinction of species would be like regardless of whether the cause was due to climate change, cycles, or environmental negligence. I anticipated the resulting paintings would be depressing but actually found them to be quite the opposite, even beautiful yet haunting. This inspired a series of large and small paintings, several lithographs and a sculpture based on this idea that beautiful places and wildlife that inhabit them are threatened, and a world without wildlife would be like a world without color.

PK: Can you briefly explain your exhibit title Penumbra in relation to the works included?

BH: The word penumbra refers to “the partially shaded outer region of the shadow cast by an opaque object.” (New Oxford American Dictionary) In astronomy, it refers to the shadow cast by the earth or moon over an area experiencing a partial eclipse. Both definitions relate to the work selected for the show in both poetic and literal ways. The works look shadowy as if the world has been eclipsed in some way. Metaphorically, they represent shadowy regions of our world—a transitional space between what’s true and what is perceived. It’s not strictly darkness, but the place where darkness and light meet.