Austin-based artist and musician Steve Parker examines history, systems, and behavior through interactive sculptures. Utilizing his background in art, music, and math, he creates elaborate listening and sound “machines” from found objects, electronic devices, and musical instruments. For the OJAC’s Cell Series, Parker will engage not only visitors but also the historic 1877 jail structure in which he will install his works. Parker’s creative communal projects have made him a recent recipient of the Rome Prize as well as a Fulbright Fellowship, Harrington Fellowship, and the Tito’s Prize.

Patrick Kelly, Old Jail Art Center Executive Director and Curator, email interview with artist Steve Parker (May - June, 2021)

PK: Much has happened to you and your career in the last couple of years including numerous prestigious awards like the recent Rome Prize and a Tito’s Visual Arts Prize, not to mention solo shows. Mixed in all this was a pandemic. Can you briefly talk about the art work you were doing up until early 2020 and if, or how, the pandemic has altered your artistic practice?

SP: Prior to 2020, I was focused on making sculptures that created performances with viewers. In these works, the sculptures were activated by people in different ways: by touch, by listening, and sometimes by wearing the sculptures. As a result, the objects created spontaneous sonic events, where visitors to the gallery were engaged as performers and, in turn, viewed by other viewers.

I'm still trying to figure out how the pandemic has altered my artistic practice. Of course, there are obvious ways in which my work shifted as a result of public health concerns, like avoiding gathering large groups of people together in tight spaces to make sound. Though on a deeper level, I've found myself gravitating more toward themes of loss, intimacy, and the fragility of the human body. This has led me to create some new figurative work that examines the close ways we listen to the bodies of our loved ones. Another work looks at ways we can sing together and engage in group rituals while physically isolated.

PK: Your artistic practice employs some fairly sophisticated technology, engineering, and skillful fabrication…not to mention the musical aspects. I understand you have degrees in math and music that you can tap into, but where do the other required skills derive?

SP: I'm an improviser at heart and most of my technical "skill" is derived from experimentation and online tutorials. I doubt that makes me unique as an artist—most of us are constantly hacking and playing around with new materials. Above all, I try to be sensitive to the objects that I'm working with and respond to their tendencies and idiosyncrasies.

PK: You often work with musical instruments…usually brass horn types, it seems. Do you remember the first one you created as a work of art and what informed or inspired its creation?

SP: My interest in working with musical instruments stems from the practice of utilizing extended techniques—that is, playing the instrument in unconventional ways, adding other objects to performances, and really, just hacking it and playing it wrong. So, it's been a gradual evolution from manipulated instruments in a performance context to creating objects/sculptures from musical instrument parts. I suppose the first time I did this for a gallery/museum situation was for a show at Austin’s grayDUCK Gallery Crit Group exhibit in 2017. For this, I created a functionally impossible brass instrument from salvaged parts and repurposed it as a controller that triggered different audio samples that were played through the resonant bodies of the instrument. Since then, I've continued to be interested in making sculptures that facilitate some sort of performance with viewers, blurring the lines between composition, instrument, performer, and listener.

PK: You have also introduced some historical and non-musical sounds into works. Can you discuss one or two of those examples and their means of delivery?

SP: Lately, I've been interested in looking at the history of sound in conflict. This has led me to examine two specific examples of WWII history: The Ghost Army and acoustic locators.

The Ghost Army was an Allied tactical deception unit during World War II. Their mission was to impersonate other Allied Army units to deceive the enemy. From a few weeks before D-Day, when they landed in France, until the end of the war, they put on a "traveling road show" utilizing inflatable tanks, sound trucks, fake radio transmissions, scripts, and sound projections. The unit was an incubator for many young artists who went on to have a major impact on the post-war US, including Ellsworth Kelly, Bill Blass, and Arthur Singer.

Ghost Box is a playable sound sculpture modeled after a WWII-era shortwave radio. When touched, the sculpture plays different looped audio clips of coded transmissions, including Morse Code, spirituals, the Hebrew Shofar, and the Iron Age Celtic carnyx. Embedded into the sound sculpture are a series of musical scores on paper that incorporate maps and icons of the WWII Ghost Army, the functional wires of the attached electronics, and map pins.

Modeled after obsolete acoustic locators of the 1930s, Tubascope is an interactive sculpture that works like a telescope for your ears. Tubascope is made from reclaimed and repurposed brass instruments and copper tubing. Rather than produce music, the sculpture invites the viewer to engage in the simple act of focused listening.

PK: Can you talk generally about the works or theme of your Cell Series exhibit Performative Listening and perhaps specifically about one work?

SP: In Performative Listening, I'm presenting works that explore listening itself as an expressive act. Listening is a profound tool for self-care and compassion, and can also be utilized for more sinister means, if we look at its historical connection to conflict and surveillance. I'm interested in how the act of listening can be a poignant, meaningful act when it is viewed by others.

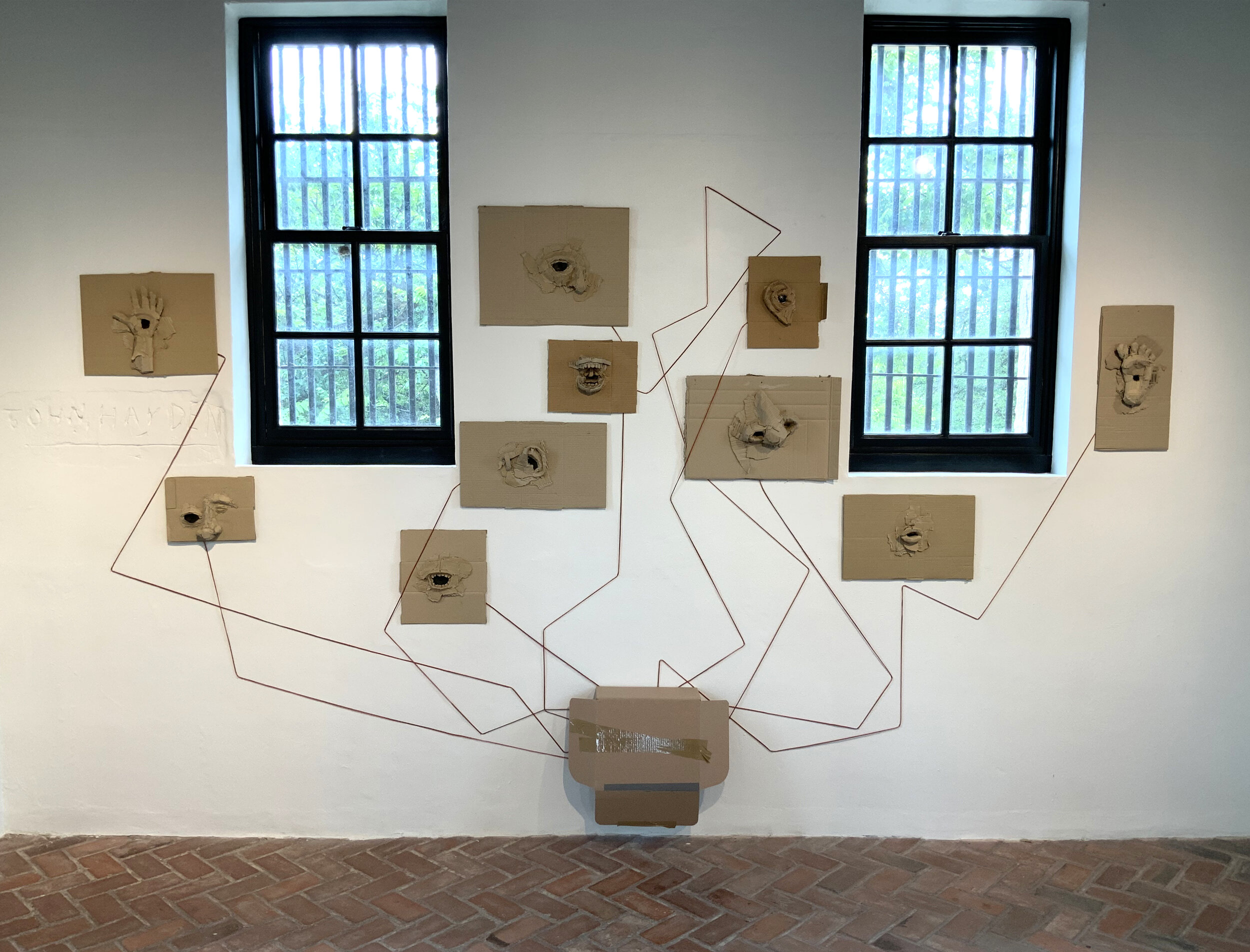

One work that speaks to this is Death Rattle, a series of sonic body parts made from cardboard. These sculptures, which reference the liturgical ex voto, have small speakers embedded in them that play sonic interpretations of body processes, exploring the intimate ways we listen to our bodies, and our loved ones, at the beginning and at the end of life.

PK: Listening seems very relevant given the context of the historic use of the jail cells. I can imagine that during its use as a means of incarceration in the 19th century, listening in isolation for months on end to your own body and things you can’t see may have been inescapable. Do you anticipate, or already recognize, any other relationships between your work and the historic space that will host your work?

SP: That's a very interesting question. Thinking about this in a more general sense, I'm drawn to the idea of the role of sound in resistance, surveillance, and persecution, particularly in the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan. So yes, I think it's powerful to consider the context of the jail cells in the presentation of this work and how sound, and listening in particular, can be a tool to examine some of these ideas.

The 2021 Cell Series is generously supported by McGinnis Family Fund of Communities Foundation of Texas, Kathy Webster in memory of Charles H. Webster, National Endowment for the Arts, with additional funding from Jenny & Rob Dupree